Field Visit

12/05/2025

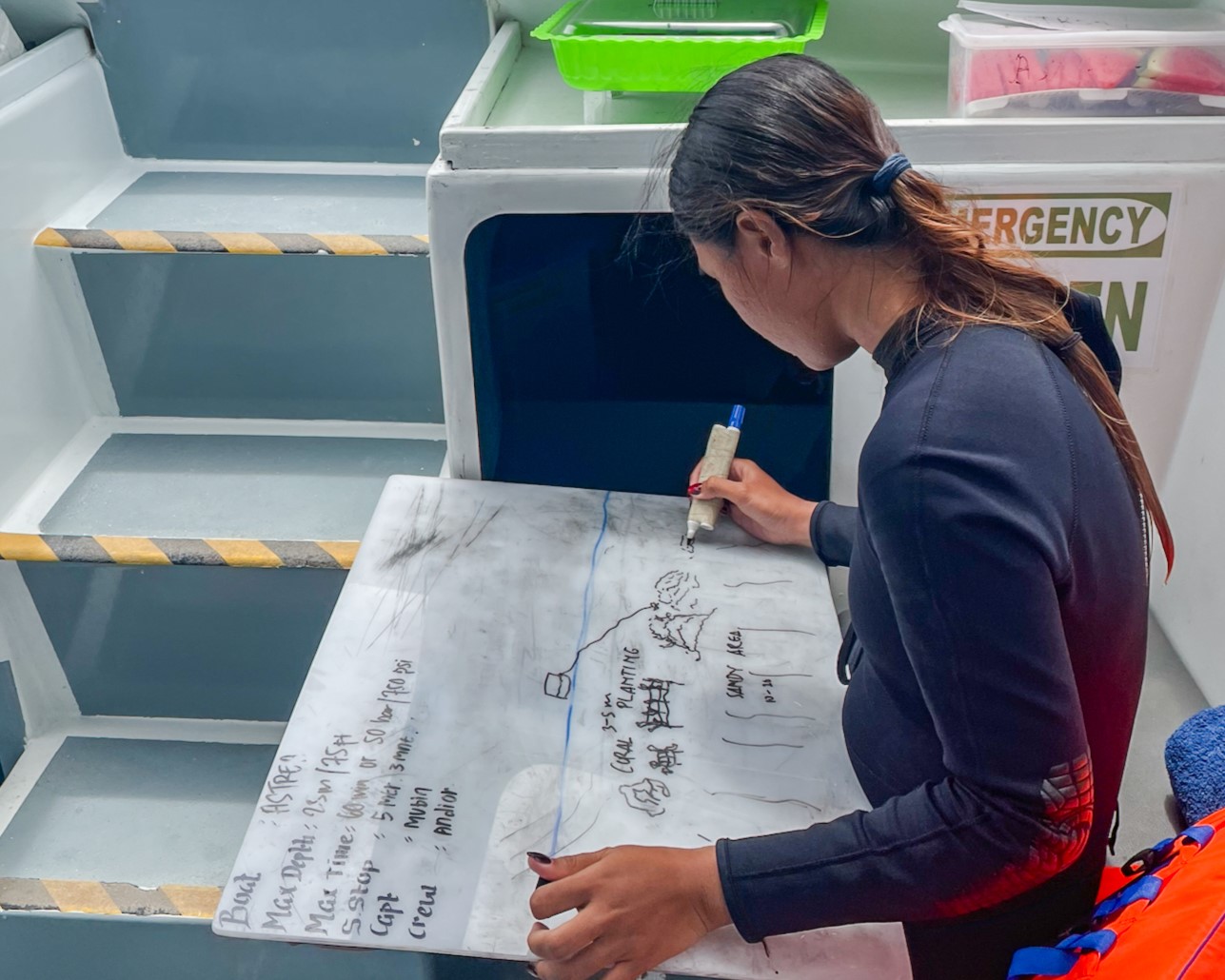

Indonesia: Inspecting the Mechanics of Coral Reef Conservation

Senior Programme Manager Nina Saalismaa travelled to Indonesia to see how the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) is using the Foundation’s support to protect ecosystems and build sustainable livelihoods in the coral-rich Sulu-Sulawesi Seascape, which also includes parts of Malaysia and the Philippines.

We can no longer avoid the climate change that is already killing and bleaching reefs around the world. But we can reduce the impacts from pollution, overfishing, coastal development and unsustainable tourism to give the more resilient corals a chance to survive, and to continue to support the well-being of so many people.